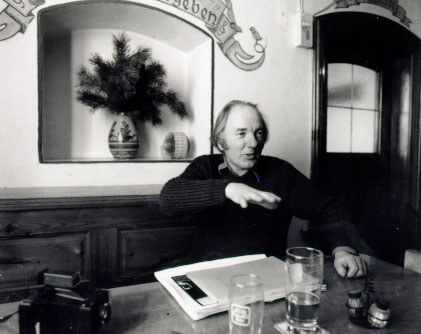

If one tries to approach Thomas Bernhard by way of archive material,

one enters a complicated situation. Instead of the one writer one had

dealt with as a reader, one has a great number of different Thomas Bernhards

in your luggage to Vienna: the "great stubborn loner," the

"humorous tragedian," the "macabre humorist," the

"suffering rebel" (Reich-Ranicki), the "state-qualified

misanthrope" (Ulrich Weinzierl), the "virtuoso of desperation

and mannered moroseness" (Eberhard Falcke), the "comedian

infatuated with gloom" (Franz Josef Görtz) or the "misanthropic

word mill" (Sigrid Löffler).

Reading the criticism of his many volumes of prose and the frequently

performed plays is like the changing consumption of something sweet

and sour. And then one sits in front of mirrored pillars in a hotel

in Kärtner Straße and waits for the poet. Maybe he has discovered

you in the mirror long before and had found you as repulsive as Cäcilia

and Amalia in "Extinction." Maybe that's the reason he has

left again a long time ago. But then there he is, and his open smile

extinguishes all portraits one has read about. One wants to know from

him: Who is Thomas Bernhard?

Thomas Bernhard: One never knows who one is. The others tell

you who you are, don't they? And as you're told so a million times if

you live a long life, in the end you don't know at all who you are.

Everyone says something different. You yourself also say something different

each new moment.

Asta Scheib: Are there people on whom you depend, who influence your life

in a decisive way?

TB: One always depends on people. There is no one who doesn't depend

on somebody. Someone, who is always alone with himself, will go under

in no time, will be dead. I believe there are decisive people for everyone.

I had had two in my life. My grandfather on my mother's side and another

person, someone, whom I got acquainted to one year before my mother's

death. That was a relation that lasted over thirty five years. It was

the person everything concerning me related to, of whom I learnt everything.

With the death of that person everything was gone. You are alone then.

First you also want to die. Then you search. You had turned all people

you also had in life into something less important during your life.

Then you're alone. You have to cope.

When I was alone, no matter where, I always knew, this person protects

me, gives me support, but also dominates. Then everything is gone. You

stand there in the cemetery. The grave is covered with earth. All that

meant something to you is gone. Then each day in the morning you wake

up with a nightmare. It's not like you really want to live on. But you

don't want to hang or shoot yourself either. You think that's not nice

and unappetizing. Then you only have books. They swoop down on you with

all the terrible things you can write into them. But you act your life

to the outside world as if nothing had happened, because otherwise you

would be devoured by the world. They are just waiting to see you show

weakness. If you show weakness it will be exploited shamelessly and

will be drenched in hypocrisy. Hypocrisy means pity. That's the best

term for hypocrisy.

But it is, as I said, difficult; after thirty-five years together with

someone else you are suddenly alone. Only people who have gone through

something similar will understand that. Suddenly you are one hundred

percent more distrustful then before. Behind each so-called human utterance

you suspect some meanness. You become even colder than people thought

you had always been before anyway. The only thing that saves you is

that you cannot starve to death. Such a life surely isn't pleasant.

Then there is your own frailty. A total decline. One only enters houses

with a lift. One drinks a quarter of a liter at noon, and a quarter

in the evening. Then you get somehow through the day. But if you drink

half a liter at noon that night will be terrible. Those are the problems

life shrinks to. Take pills, don't take them, when to take them, what

to take them for . Each month you are driven a little nearer to craziness,

because you are confused.

AS: When did you last feel happy?

TB: One feels happiness each day, you're happy to be alive and not

dead already. That's a great capital.

From the person who died, I know that you love life to the very last

moment. Basically, everyone loves to live. Life cannot be so terrible

that you don't keep on with it after all. The motivation is curiosity.

You want to know: what will come next? It is more interesting to know

what will come tomorrow then what is here today. When the body is ill

the brain develops astonishingly well.

I prefer to know everything. And I always try to rob people and get

everything that is in them out of them. As long as you can do so without

the others recognizing it. When people discover that you want to rob

them they shut their doors. Like the doors are shut when someone suspect

comes near. But if nothing else is possible you can also break in. Everyone

has some cellar window open. That also can be quite appealing.

AS: Did you ever want to have a family?

TB: I was always happy to survive. I couldn't think of founding

a family. I wasn't healthy, therefore I didn't feel like doing these

things. There was nothing left for me but to flee into my mind and to

start something on that basis, the body didn't have any potential. It

was empty. It stayed like that through decades. Whether that is good

or bad one doesn't know. It's one way to live. Life knows billions of

different existences.

My mother died when she was forty-six years old. That was in 1950. A

year before I had got acquainted with my life partner. First it was

a friendship and a very close relationship to a person who was much

older than I was. Wherever I was on earth, she was the central point

from which I took everything. I always knew: this person is there for

me one hundred percent if things get difficult. I only had to think

of her, I didn't even have to visit her, and everything was already

in order. Now too I live with that person. If I have problems I ask:

what would you do? By that I'm held back from disgusting things which

one might still commit at an older age, because everything is possible.

She is the one keeping me from doing certain things, teaching me discipline,

but also the one opening the world to me.

AS: Have you been content with your life at some moment in that

life?

TB: I have never been content with my life. But I always felt a

great need to be protected. I found that protection with my friend.

She always got me working. She was happy when she saw that I was doing

something. That was great. We traveled together. I carried her heavy

bags, but I got to know a lot. As far as one is able to say so of oneself,

it's always not very much, almost nothing. For me it was everything.

When I was nineteen she showed Sicily to me, the place where Pirandello

lived. She wasn't eager to stuff a lot of learning into me. It just

happened. We stayed in Rome, in Split -- but then the journeys more

and more often changed into inner journeys. We were somewhere in the

country where one lives very simply. Where at night it snowed in onto

the bed. There was the tendency to simplicity. The cows lived right

beside us, we ate our soup and had a lot of books with us.

AS: Have you accepted your existence as a writer?

TB: Well, one wants to get better at writing, because otherwise

you become crazy. That happens when you get older. The composition should

always get more concise. I always tried to do something better when

going on. To take the next step depend on the one before. Of course

one always has the same theme. Everyone has his theme. He should move

around in that theme. Then he does it well. There were many ideas. Maybe

one wants to become monk, or work on the railroad, or cut wood. One

wants to belong to the very simple people. That's of course a mistake,

because you do not belong. If one is like I am something like that is

of course impossible, one cannot be a monk or work on the railroad.

I was always a loner. Despite that one strong relationship I was always

alone. At the beginning of course I thought I had to go somewhere and

join in the conversation.

But since almost a quarter of a century ago I haven't hadcontact with

any other writers.

AS: One of your central themes is music. What does music mean to

you?

TB: When I was young I studied music. It had pursued me since my

childhood. Although I loved music it was like being hunted, chased.

I only studied to be together with people of my age. And the reason

was this older person. With my colleagues at the Mozarteum I played

music, sang, performed. Then music was no longer possible because it

wasn't possible physically. You can only make music if you are together

with people all the time. As I didn't want that, that was that.

AS: Your invectives, attacks against the government, the church,

are very harsh at times. Catholicism is described as "destroyer,

frightener, character destroyer of a child's soul" in Extinction.Your

country Austria has become to you "an unscrupulous business where

all that is done is bargaining and swindling." Do you write this

out of some kind of universal hatred?

TB: I love Austria. I cannot deny that. The construction of government

and church -- that's the terrible thing, you can only hate that. I think

all countries and religions you know well are similarly disgusting.

After some time you see that the constructions are all the same, dictatorship

or democracy -- for the individual all is disgusting to the same degree.

At least when you look close.

AS: Isn't it important to you to be accepted as a writer in your

home country?

TB: The human being naturally longs for love, from the beginning.

Love the world has to give. If one does not get it the others can say

a hundred times that you are cold and don't see and hear that. It's

very hard for you. But it's also part of life, you cannot escape from

it. If you call into a forest the echo comes back. Basically one loves

hatred after all.

AS: Is it correct that first of all you begin with a blank slate

in your books? You seem to settle up with certain people. Do you have

to pay for it?

TB: Yes. Sometimes it's almost unbearable. Yesterday a woman almost

jumped at me when I was in town. She screamed: "If you go on like

this you are going to end up in a slow and horrible death!" You

cannot do anything against such things. Or you are sitting on a park

bench and all of a sudden you are hit from behind, you give a start

and hear someone shout: "Just go on like that!" One causes

all that oneself. But one didn't expect it. In Ohlsdorf, my real residence,

I can hardly live any more. The attacks from all sides are unbearable.

But praise is equally terrible, hypocritical, untruthful, and egoistic.

People get nasty when I don't open at once, they break the windows.

First they knock, then they shout, then they scream, then they break

the window. Then the engines of their cars roar, then they are gone.

Twenty-two years ago I was so stupid and made my address known, now

I can no longer live in Ohlsdorf. People are sitting on the walls there;

already in the morning when I go out the door they are sitting there.

They want to talk to me, they say. Or at weekends people instead of

going to the zoo go out to look at a poet. And it's cheaper. They drive

to Ohlsdorf and position themselves around the house. I look out like

a prisoner or a lunatic. Unbearable.

Since twelve years agp I haven't given readings. I can no longer sit

down and read my own stuff. I also cannot bear people applauding. Applause

- actors are paid in such a way. They earn their money in such a way.

I like it when the money from my publisher arrives on my account. But

marching music, hosts of applauding people in the theater or in the

concert -- I can't bear that. Nothing but disaster follows from applause.

AS: In Extinction you said that at the age of 40 one should

be proclaimed a wise old fool [Altersnarr]. Why?

TB: That method is the only one that makes things bearable. You

have asked me how I see myself. I can only say: as a fool, a jester.

Then it's bearable. Only when seeing oneself as a fool, an aged fool.

A young fool is not interesting. He isn't accepted as a fool anyhow.

AS: Was what you were writing earlier in you life, say 'The Breath"

or 'The Cold," also a means to come to terms with your illness?

TB: My grandfather was a writer. Only after his death I really dared

to write myself. When I was eighteen a commemorative tablet was unveiled

in my grandfather's home town. After the ceremony everbody went to a

restsurant that belonged to my aunt. I was also there and my aunt told

the journalists that were present : "This is his grandson, he won't

achieve anything in life. But maybe he can write." One said: "You

can send him in on Monday." And I got an order to write something

about a refugee camp. The next day my text was in the newspaper. Never

again in my life did I experience such exaltation. A really great feeling

that you write something and after one night it is printed even if abridged.

But it was in the newspaper. By Thomas Bernhard. I had tasted blood.

I wrote court reports for two years. They were in my head when later

I wrote my own prose, that's where the origins lie.

AS: How do you feel today when critics like Reich-Ranicki or Benjamin

Heinrichs write admiringly about you? Do you feel exaltation?

TB: When reading criticism I now never feel exaltation. At the beginning,

yes, because you believe all these things. But experiencing the ups

and downs for thirty years, then you look through the mechanisms. One

sends a servant saying: "Go write a negative critique." That's

how it works

AS: Are you annoyed at negative criticism?

TB: Yes. Even today I fall into every trap. I have always been fascinated

by newspapers, that was starting very early. I can hardly bear a day

without a newspaper. After some time you know the editors of the various

newspapers. Maybe I haven't seen them, but I know about the situation

at a theater, the background in an editorial office, I know publishers,

their manuscript readers, their business. The intellect always comes

to grief. Taste comes to grief. Poetry comes to grief. Columns of editors

ride over it. They stop at nothing creative. That's also in a way fascinating.

It hurts me but it no longer disturbs me in my work.

AS: In one of your speeches you once said: "We have to report

about nothing but the fact that we are wretched." Do you write

in order to testify to your failures?

TB: No, I do everything for myself. All people do so. Whether they

are rope-dancing or baking bread or conducting a train or whether they

are stunt pilots. Though stunt pilots have performances where people

look up. While he flies beautifully they wait for his fall. It's the

same with writers. But other then the stunt pilot, who is dead when

that happens, the writer will also be dead but will always start again.

There is always a new performance. The older he gets the higher he flies.

Until one day you can't see him any longer and ask: "Strange, why

doesn't he fall down?"

Writing delights me. That's nothing new. That's the only thing that

still supports me, that will also come to an end. That's how it is.

One does not live forever. But as long as I live I live writing. That's

how I exist. There are months or years when I cannot write. Then it

comes back. Such rhythm is both brutal and at the same time a great

thing, something others don't experience.

AS: Women in your books are, apart from a few exceptions, not drawn

in a very friendly way. Is that your experience?

TB: I can only say that for a quarter of a century I have dealt

with women only. I can hardly bear men. I can't bear conversations with

men. They drive me crazy. Men always talk about the same things. About

their job and about women. You cannot expect anything from men. A lot

of men in one place are terrible. I even prefer gossiping women. Relating

to women had always been useful to me. I learnt everything from women

-- and my grandfather. I don't believe I learnt anything from men. Men

have always gotten on my nerves. Strange. After the death of my grandfather

there was just nobody there any longer. I always sought protection with

women, who in many things were also superior to me. Above all women

let me work in peace. I was always able to work near women. I could

never produce anything near men.

AS: After the death of your friend is there anybody you wouldn't

want to miss?

TB: No. I mean, there are hundreds of people, I could dance at a

thousand marriages, but there is nothing I would despise more. Recently

I dreamt that the lost person is back. I said, all the time you weren't

here was terrible. As if that time had been some interim time and the

dead person would now live on. That was very intense. You can't get

that back. It's no longer possible. Now I take the position of an observer

of only a narrow territory from where I look at the world. That's all.

AS: Do you believe that there is an existence after death?

TB: No. Thanks God. Life is wonderful. But the best thought is that

when it ends it ends forever. That's the greatest consolation to me.

But I really enjoy living. It was always like that, except those times

when I thought of suicide. That was when I was nineteen, at twenty-six

quite strongly, again at the age of forty. But now I love life. If you

see someone who has to leave, but still is in this life, then you start

to understand that.

One of the most marvelous things I experienced was that you hold another

one's hand in your hand, you feel the pulse, then it becomes slower

and slower, then that's it. It's something enormous. Then you still

hold that hand, then the nurse comes in, bringing with her the number

for the corpse. The nurse wheels her out once more and says: "Come

back later." Then you are immediately confronted with life again.

You calmly get up and put things in order; in the meantime the nurse

comes back and attaches the number to the corpse, you empty the bedside

cabinet, the nurse says: " Don't forget the yogurt, you have to

take it too." Outside you hear the crows -- it's like a theatrical

play.

Then the bad conscience comes. A dead person leaves you with an immense

guilt.

All the places I had stayed with her, places I wrote about in my books,

I can no longer visit. Each of my books was created at a different place.

Vienna, Brussels, somewhere in Yugoslavia, in Poland. I never had a

desk in mind. When writing was going well it didn't matter where I did

it. I also wrote with the greatest noise around me. I'm not disturbed

by a crane or a noisy crowd or a screaming tram, or a laundry or a butcher's.

I always liked to work in a country where I didn't understand the language.

That was stimulating. A strangeness where you are one hundred percent

at home. For me it was ideal to live together in a hotel, my friend

took walks for hours and I was able to work. We often met for meals

only. She was happy when she recognized that I was working. We stayed

up to four or five months in a country. Those were highlights. While

writing you very often have a very good feeling. If in addition to that

there is someone who appreciates that and who leaves you in peace --

that's ideal. I never had a better critic. You cannot compare that to

a dumb public critique that never looks deep into the text. This woman

always provided a very strong positive criticism that was very useful

to me. She knew me with all my weaknesses. I miss that.

I still like to be in our apartment in Vienna. I feel protected there.

Maybe because we had been living there together for years. Now it's

the only nest of our togetherness. The cemetery is also not very far

away.

In life it's a great advantage if you have already experienced something

like it. Things don't affect you as much after that. You're neither

interested in failure nor success, neither the theater nor the directors,

nor the editors or critics. You aren't interested in anything. The only

interesting thing is that there is money on your account so that you

can live. My ambitions were no longer as great as they had been earlier.

After her death that ceased entirely. I'm not impressed by anything

any more. One still likes some old philosophers, some aphorisms. It's

almost like fleeing into music. For hours you enter into a wonderful

mood. I still have plans. I once had four or five, now I have two or

three. But it's not necessary. I don't need it and the world doesn't

need it either. When I feel like writing I write, when I don't feel

like it I don't. Whatever you write it's always a catastrophe. That's

the depressing thing about the fate of a writer. One can never put on

paper what one thought of or imagined. That gets lost when it is put

onto paper. All you deliver is a bad, ridiculous copy of what you had

imagined. Basically, one cannot communicate all that. No one ever managed

to do so. It's especially hard in the German language because that language

is wooden and clumsy, disgusting. A terrible language that kills everything

light and wonderful. The only thing one can do is sublimate that language

with a rhythm to give it musicality. When I write it's in the end never

what I had thought it would be like. That's less frustrating with books

because you think the reader has her own imagination. Maybe the flower

will blossom after all, will unfold its leaves. In the theater only

the curtain unfolds. Those are human actors who suffered for month before

the first performance. Those people were meant to be the persons one

had made up. But they are not. The persons in your head, that had been

able to do everything, are of blood and flesh all of a sudden, water

and bones. They are clumsy. In your head the play was poetic, great,

but the actors are business-like translators. A translation doesn't

have a lot to do with the original. So the play that is performed in

a theater does not have a lot to do with what the author had created.

The stage, the boards were to me boards that always destroyed everything.

All is trampled down. Each time it's a catastrophe.

AS: But you continue writing. Books and plays. From one catastrophe

to the next.

TB: Yes.

|